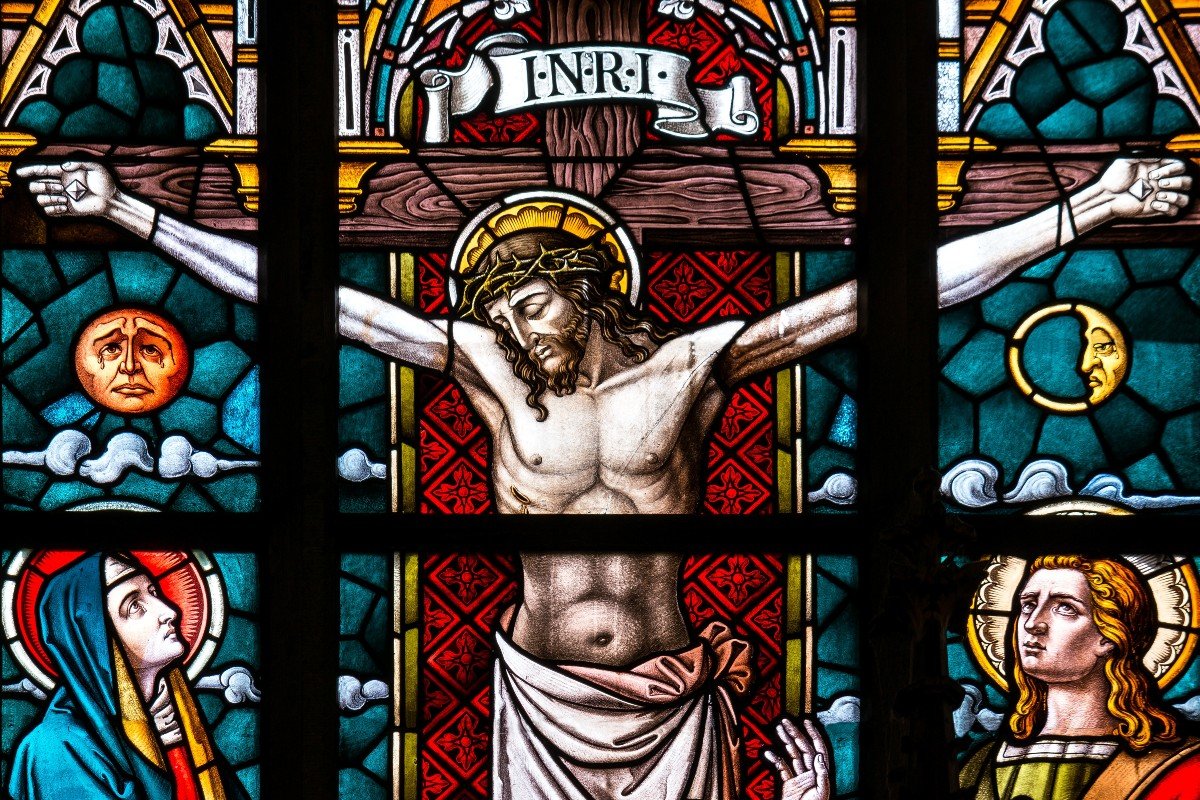

“Good” Friday

good adj. better, best a) a general term of approval or commendation; b) suitable to a purpose; effective; c) producing favorable results; beneficial

The amazing thing about Good Friday is that it was – and is – part of the “good” declared by God at creation. “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good” (Genesis 1:31, NIV). The Fall was not good; sin, disobedience and suffering are not good. But God’s purpose in creation and the redemptive drama that ensued were – and are – good.

Some would put God in the dock for placing such a burden on human life—that through our creation and giving us free will He knew the suffering we would experience. What is less noticed is how God always knew of Good Friday. In the rapture of creation, the cross loomed large. Yes, there would be suffering, but none more so than for God Himself.

C.S. Lewis writes:

God, who needs nothing, loves into existence wholly superfluous creatures in order that He may love and perfect them. He creates the universe, already foreseeing—or should we say “seeing”? there are no tenses in God—the buzzing cloud of flies about the cross, the flayed back pressed against the uneven stake, the nails driven through the mesial nerves, the repeated incipient suffocation as the body droops, the repeated torture of back and arms as it is time after time, for breath’s sake, hitched up. If I may dare the biological image, God is a “host” who deliberately creates His own parasites; causes us to be that we may exploit and “take advantage of” Him. Herein is love. This is the diagram of Love Himself, the inventor of all loves.

What an ultimate “good” this must have been; declared at creation, consummated on Golgotha. But it wasn’t a good designed for God. There is no good to be added, or deficit to be addressed, in His being.

It was a good for us.

Many books have come out of late portraying the heart of God toward us as a lover pursuing the beloved, a fairy tale where God is the prince and we are the maiden. “Suppose there was a king who loved a humble maiden,” begins Soren Kierkegaard, who first fashioned the popular analogy.

The king was like no other king. Every statesman trembled before his power. No one dared breathe a word against him, for he had the strength to crush all opponents. And yet this mighty king was melted by love for a humble maiden. How could he declare his love for her? In an odd sort of way, his kingliness tied his hands. If he brought her to the palace and crowned her head with jewels and clothed her body in royal robes, she would surely not resist—no one dared resist him. But would she love him?

She would say she loved him, or course, but would she truly? Or would she live with him in fear, nursing a private grief for the life she had left behind? Would she be happy at his side? How could he know? If he rode to her forest cottage in his royal carriage, with an armed escort waving bright banners, that too would overwhelm her. He did not want a cringing subject. He wanted a lover, an equal. He wanted her to forget that he was a king and she a humble maiden and to let shared love cross the gulf between them. For it’s only in love that the unequal can be made equal.

Yes, this is the heart of God, and He is on just such a mission.

But the deeper truth lies in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. We are not a beautiful maiden. There is nothing becoming in us whatsoever. Instead, we are desperately criminal, and the only rescue grace would bring would demand storming the Bastille in which we are rightfully held. This is precisely what He did. “Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous man, though for a good man someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8-9, NIV).

And that’s an even better story. And it’s the one story that the world does not already have, and most needs to hear.

James Emery White

Editor’s Note

This blog was first published in 2005 and has been offered annually on or near Good Friday.

Sources

Webster’s New World Dictionary, Second College Edition.

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves.

Victor Hugo, Les Miserables.

Soren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments.